MAINLINE ROUTE (Source = 1918 and 1919 maps)

Compiled by Jim Ross

Missouri

1918

St. Louis

Gray Summit

Union

Leslie

Gerald

Rosebud

Owensville

Rolla

Vienna

Dixon

Crocker

Richland

Stoutland

Lebanon

Longlane

Buffalo

Fairgrove

Springfield

Republic

Mt. Vernon

Sarcoxie

Joplin

(Italics = off 66 corridor)

1919

St. Louis

Gray Summit

Union

Sullivan

Bourbon

Leasburg

Cuba

Rolla

Edgar Springs

Licking

Houston

Cabool

Mountain Grove

Norwood

Mansfield

Seymour

Fordland

Springfield

Republic

Mt. Vernon

Sarcoxie

Joplin

Not Mainline route in 1918 or 1919 but showing on Joplin obelisk: Webb City, Carterville, Carthage. Possible spur from Sarcoxie, or alternate or later mainline from Springfield via Halltown, Phelps, Avilla, etc.

Kansas

Galena

Riverton

Baxter Springs

Note: not shown on maps other than Galena, possibly due to scale, but indicated on obelisks in both Miami and Joplin

Oklahoma

Hockerville

Quapaw

Commerce

Miami

Narcissa

Bluejacket (pyramid was 4 miles west)

Centralia

Nowata

Talala

Oologah

Collinsville

Owasso

Dawson (Tulsa metro)

Tulsa

Bowden

Sapulpa

Kellyville

Bristow

Depew

Stroud

Davenport

Chandler

Wellston

Luther

Jones

Spencer

Oklahoma City

Tuttle

Amber

Chickasha

Verden

Anadarko

Washita

Ft. Cobb

Carnegie

Mountain View

Gotebo

Hobart

Lone Wolf

Granite

Mangum

Reed

Vinson

Madge

(1919 Route Same to OKC, then to Chickasha via Norman)

(A 1919 Farmers Route between Anadarko and Hobart paralleled to the south, likely

through Apache and Boone.)

1919 Split Route from Chickasha to Texas line.

Cement

Fletcher

Lawton

Cache

Snyder

Headrick

Altus

Duke

Gould

Hollis (and then Wellington, TX)

Texas

Wellington

Quail

Clarendon

Goodnight

Claude

Washburn

Amarillo

Bushland

Wildorado

Vega

Adrian

Glen Rio

(both 1918 and 1919)

New Mexico

Glen Rio

Endee

San Jon

Tucumcari

Montoya

Newkirk

Cuervo

Los Tanos

Santa Rosa

Anton Chico

Las Vegas (actually Romeroville)

(both 1918 and 1919)

Additional Notes on Routes and Maps

On the 1918 and 1919 route book maps, in addition to the mainline routes, there are numerous branches depicted, some designated, some proposed, some marked, some not.

Re: Post- 1918 and 1919 route maps, additional branches and spurs were added while others were modified.

An eastern branch to the mainline from Tulsa went through Catoosa, Claremore, Salina, and then into AR.

A branch from Chandler, OK, to Shawnee and Sulphur is noted by Nan Marie Lawler in her 1977 masters thesis, though not showing on maps.

Stroud, OK, became part of the OT in 1915.

The 1919 Route Book map shows Joplin NW to Crestline and then S. to Lowell and Baxter, rather than due west to Galena, however obelisks in Miami and Joplin, built before 1919, list Galena.

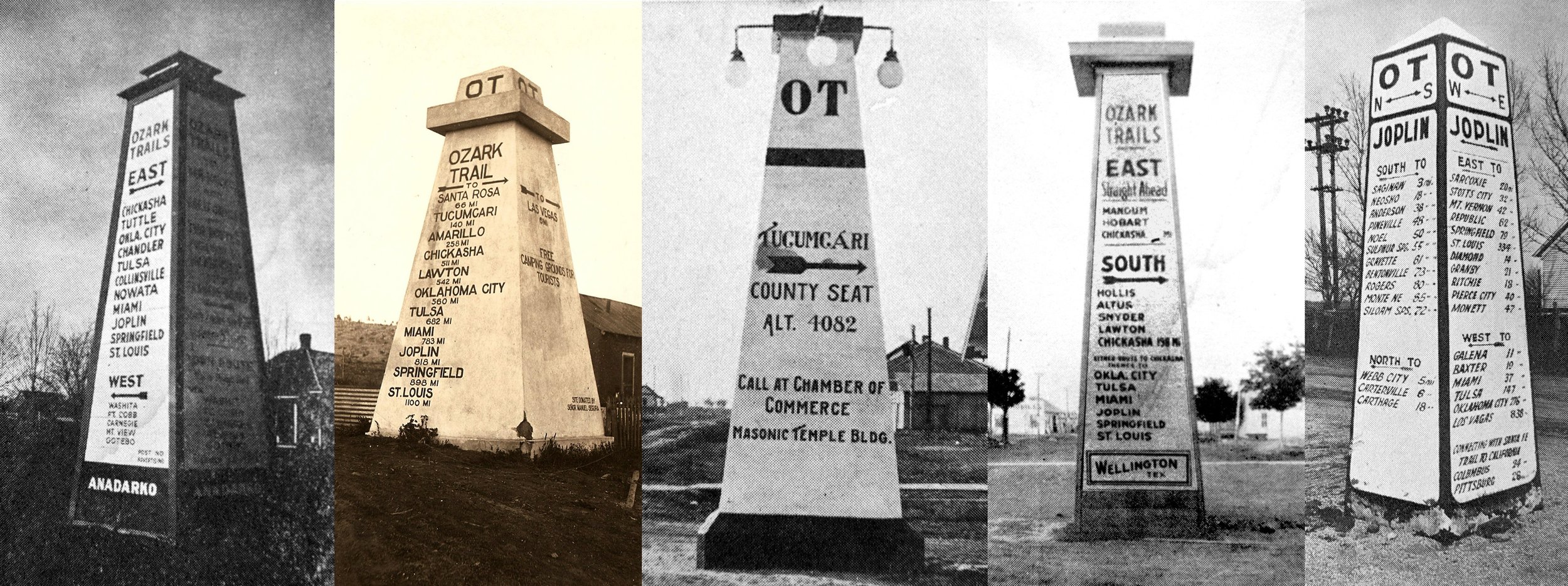

OBELISKS

Three of the seven surviving obelisks are on routes not showing on the 1918 and 1919 maps—those being Tulia and Dimmitt, Texas, and Lake Arthur, NM.

While Tampico, TX is not noted on the maps, the route between Wellington and Turkey is.

Obelisks were referred to by the OTA as “pyramids” or “monuments.”

Obelisks were conceived around 1917 and most built between 1918 and 1922. Cost was about $250 each.

They were first mentioned in the May 10, 1918 Miami Record-Herald. Typical was 4ft.Sq.Base; 2ft.Sq.Top; 20 feet tall. Some concrete, some wood, some stucco; not standardized until 1919 w/ light added and a design change on the base.

In 1919, there were two routes into NM from Texas—the original from Wellington to Amarillo, Tucumcari and Las Vegas, and one from Wellington to Roswell via Littlefield and Kenna. Meanwhile, Clovis and Portales, as well as Texas towns such as Tulia, Dimmit, etc. had been bypassed (this was known as the “northern” route). Promoters of this route, led by Tulia’s J.E. Swepston, built 16 obelisks along this path.

CONVENTIONS

1913 – Monte Ne, AR (July)

Neosho, MO (November)

1914 – Tulsa

1915 – Independence, KS (about 50 delegates)

1916 – Springfield, MO (over 3,000 delegates)

Oklahoma City – Adjourned Session (biggest with 7,000 delegates)

1917 – Amarillo, TX (only somewhat less than OKC)

Jonesboro, AR – Adjourned Session (2,000 delegates)

Chanute, KS – Adjourned Session

1918 – Miami, OK (well attended)

1919 – Roswell, NM (low attendance)

1920 – Pittsburg, KS (light attendance)

1921 – Shawnee, OK (attendance not known)

1922 – Sulphur, OK (about 1,000, most locals)

1923 – Joplin, MO – (only about 100 members attended)

1924 – Duncan, OK (less than 100)

Until 1918, several conventions were actually held each year, in different states; one general and the others “adjourned sessions.”

1917 Amarillo convention was to select official route.

Campaigns for conventions and routes were competitive and carnival-like. Conventions were used to elect officers, decide on routes, and select location of next convention.

Documented locations of obelisks

Surviving

SW of Stroud, OK (On NRHP; not moved, as suggested by Cassity)

Langston, OK

Wellington, TX – Possibly originally wood for inclusion in log book, then built of concrete; removed about 1939 and dumped in a field. Recovered in the mid-1980s, rededicated on 9-12-1990.

Tampico, TX

Tulia, TX (1920)

Dimmitt, TX - Moved

Lake Arthur, NM (1921 – on National Register)

Documented in photos

Dawson, OK, 9 mi. E. of Tulsa at jct. with mainline from Collinsville & the branch through Claremore to AR

Miami, OK (2)

Tucumcari, NM

Anadarko, OK

Bluejacket, OK (Wood – 4 mi. W. of town crossroad at jct. with Jefferson Highway)

Joplin, MO

Referenced in Literature

East of Hobart, OK

Miami, OK (#3)

Las Vegas, NM (Romeroville)

Chickasha, OK (1919)

Stroud, OK (1920 - in the city)

Lowell, KS

Buffalo, MO

Quitaque, TX

Artesia, NM

Carlsbad, NM

Lakewood, NM

4 on the Pecos Branch of Pecos Valley Route (from Malaga, NM to Van Horn, TX via Pecos)

Mildred Loftin of the Swisher County (TX) Museum, citing three newspapers, states that 19 obelisks were built in Texas and two counties in NM (Curry and Roosevelt).

GENERAL

William Hope “Coin” Harvey (1831-1936) was a lawyer, real estate developer, and advocate of “free silver.” He authored books on finance and was an advisor to William Jennings Bryan during the 1896 elections. His money came from silver mining in Colorado and other projects. He was politically active, running for president in 1932 for his own Liberty party and got 54,000 votes. The nickname “Coin” came from his advocacy of financial reform and the free coining of silver.

Harvey purchased Monte Ne property (320 acres) in 1900, named it Monte Ne (“Mountain Waters” according to Harvey) and began developing in 1901. He built a 5 mile RR spur from St. Louis – San Francisco Line at the town of Lowell; guests traveled the last ½ mile by boat. He conceived OT to bring traffic from 4 states when RR went broke and was abandoned in1910.

Assn. was organized on July 10, 1913, at which time he already had a map (see Lawler, pg. 11) though he began planning as early as 1910. Its intent was to mark and connect roads in AR, OK, MO, and KS to Monte Ne. Texas,NM, Colorado and Nebraska were later added, with the main line running about 1100 miles from St. Louis to Las Vegas, NM. It was not in the business of building roads; only promoting them. OTA dues were $5.00 per year.

The main line routes were adopted in 1916 at the Amarillo convention after much competition among cities wanting the route and among promotion of different routes. A mainline was initially established, though changes would come later with splits in the mainline and new branches added, some of which came after the route books of 1918 and 1919.

Official colors of the OTA: Green and White (white field, green OT in the middle; stripe top & bottom).

US Good Roads Assn. chartered April 25, 1913. HQ was in Birmingham. Its goals were to seek federal aid and Establish a Nat’l. Hwy. Commission for building roads.

Harvey stepped down as president at the 1920 Pittsburg , KS convention, though he still called the shots. Harvey was skeptical about the future of civilization, and he next focused on a 150-tall monument in Monte Ne that would contain a time capsule explaining why civilization collapsed as well as instructions on how to rebuild and artifacts showing the state of technology of the time. It was never built. The resort property was covered by Beaver Lake in the 1960s.

By the mid-1920s, there were around 250 different named trails. (Lopez)

Harvey envisioned the OT to be a hard-surface link in an ocean-to-ocean highway. (Lopez)

Cyrus Avery was a strong supporter of the OTA, bringing their convention to Tulsa in 1914 and becoming a vice-president.

By 1916, three routes (northern, central and southern) had been proposed. Even then it was confusing; tracing them today is not possible. Final route selections were made at the 1917 Amarillo convention. This was heavily influenced by the amount of improvements made by those along the proposed routes. Generally, the more central rotue was chosen—Tulsa, OKC , Amarillo, and Las Vegas, NM, establishing a corridor for future Route 66.

At the 1918 convention in Miami, Harvey proclaimed that the OTA had 2,000 miles of adopted and marked roads and was promoting a total of 7,000 miles of roads. It was here that Harvey first proposed permanent markers on the trails, calling initially for 12 between Springfield, MO and and Las Vegas,at OT branch junctions, with a 50 ft. tall monument at Romeroville to signify the jct. with the Santa Fe Trail. Almost all were destroyed or buried within a few years of the implementation of the uniform numbering system in 1926. There is no accounting of how many were actually built. (Murphey)

At the 1919 Roswell convention, controversy erupted over a proposal to extend the route south through Artesia and Carlsbad to Van Horn, TX to connect with the Old Spanish Trail. Known as the Pecos Valley Route, at the 1920 convention this route won approval as an “altenative” route to El Paso, leaving the primary route from Roswell to El Paso via Alamogordo. Note: this route shifted in 1922 from Malaga to Pecos, TX, rather than to Van Horn, TX.

Tulia’s J.E. Swepston was elected OTA president at the 1920 Pittsburg, KS convention.

1921 Shawnee convention featured the “Chandler-to-Sulphur” branch promoters and “insurgents” from the Hobart – Mangum delegation who tried to take over the OTA to ensure they would remain on the official route. They were thrown out of the OTA.

At the 1923 Joplin, MO convention, Chandler’s J.A. “Big Mack” McLaughlin was elected president. No further conventions were scheduled.

With the coming of the numbered routes, Avery adapted the path of the Ozark Trails to his blueprint for a major Chicago-to-LA route from St. Louis to Romeroville.

About all that’s left today of the OT are some section line roads and stretches adopted by Route 66 or other state & US highways, including the a section of former US 366 between Roswell and Kenna, NM.

Parts of the OT in NM were later adopted by US routes 66, 285, and 366.

US 366 was decommissioned in 1937 and redesignated US 70. A 1921 unpaved alignment of OT/US 366 with an anonymous FAP marker remains between Elkins and Kenna, NM, now known as Railroad Mountain Road and accessed from US 70 NE of Roswell near Elkins or SW of Clovis at Kenna. Distance is 23 miles.

Midway Service Station in Kenna opened in 1938 and was originally a Phillips 66. Postmistress is Maurene Howard. (Murphey)

There is no official date of the OTA disbanding, though no conventions were held after 1924. Some researchers suggest it may have continued to operate until 1926 or even 1927.

The OTA Log Book was published in 1918 with one map, lots of ads, and directions using landmarks and mileage. The Ozark Trails Route Book was published in 1919 and contained numerous maps along with photos, ads, descriptions of towns, etc.

The OTA was one of the last Good Roads orgs, and didn’t have a significant impact. It has some influence on later roads, but not great. Was good for promoting towns and encouraging tourism.

Organizational papers of the OTA have not been found.

Mapping is not comprehensive and in places fragmented / contradictory.